- The statement notes that this exhibition showcases 12 works of prominent Iranian modern artists, but the title of the exhibition is "Nine Works of Modern Iranian Art." What is the reason for this discrepancy or contradiction in the statement and title of the exhibition?

In this exhibition, works of art from nine artists are displayed. Included among these is a set of four works by Mr. Tanavoli. This collection, from 2002, belongs to the "Heech" bronze series. These works are mentioned in the statement, and their inclusion accounts for the total of 12 works displayed.

- As stated in the statement, this exhibition aims to provide insight into the movement of modern art in Iran through the displayed artworks. Considering this approach, how were these artworks selected for the exhibition? What criteria were used for selecting these specific works, and why this number of artworks? For example, an artwork by Sirak Melkonian is included, but nothing from Marcos Grigorian. Additionally, why wasn't there an exhibition featuring works by young artists?

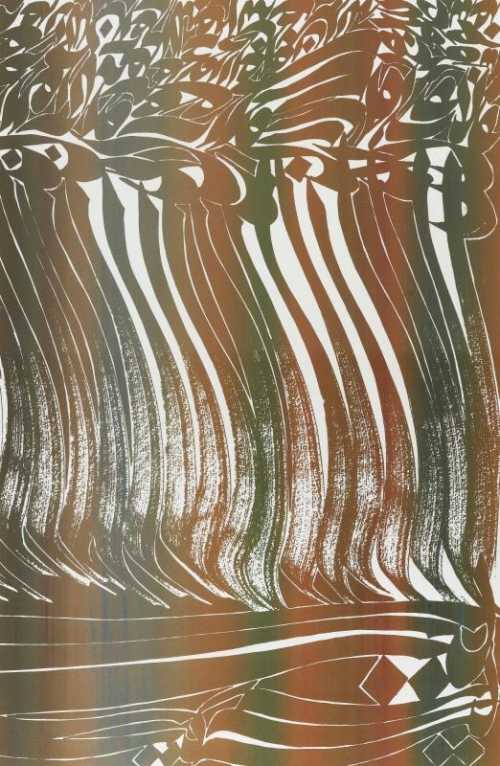

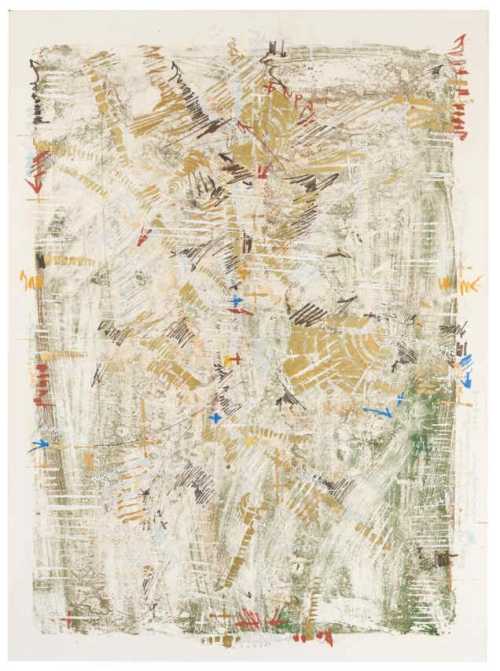

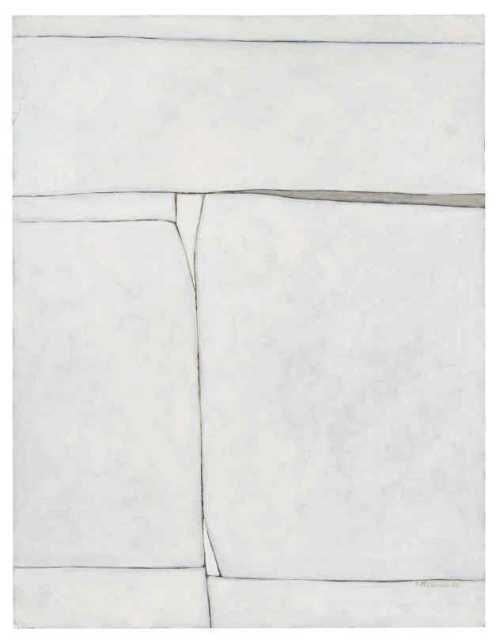

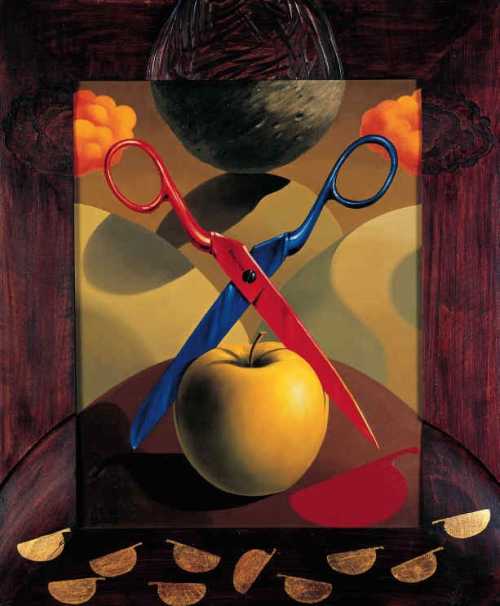

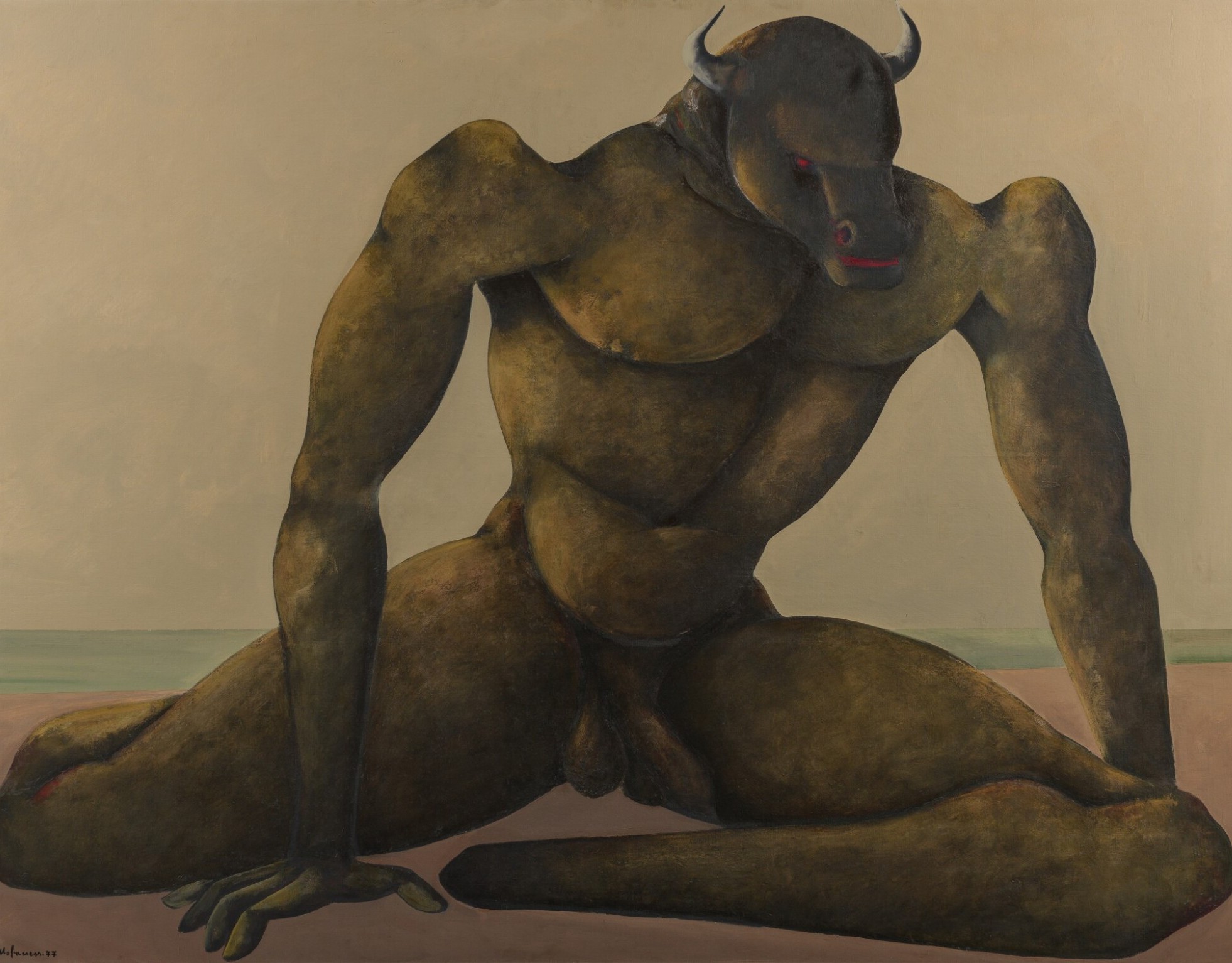

As can be seen in the photos and images, we had limited space, consisting essentially of a small gallery and one room. Naturally, if we had wanted to exhibit works by other prominent artists in this exhibition, there would have been many notable names whose works could have been included but unfortunately could not be accommodated due to space constraints. We attempted to display a selection of artworks that, in some way, represent various aspects of modern art in Iran, considering these limitations. It's a challenging task, and I don't think we necessarily succeeded because doing this properly would require a larger space. However, we aimed to gather examples ranging from abstract to figurative works, or from the Saqqakhaneh movement to contemporary calligraphy. That's why certain artworks were chosen for this exhibition.

Regarding the question of why there are no works by young artists, I must mention that this exhibition is my second collaboration with Bavan Gallery. Our first exhibition was held in October at the same venue, where we displayed works by young artists. Personally, I would love to showcase works by young artists, but since this exhibition was more focused on modernist artists, we stuck with that same generation.

- How was this exhibition held in London? Why were other cities such as Paris, Seoul, etc., not chosen for hosting this exhibition?

The exhibition was hosted at Cromwell Palace, a complex offering spaces for galleries to hold exhibitions through membership arrangements. My friend and colleague, Mrs. Ayoubi from Bavan Gallery, is a member of this complex, allowing them to organize two to three exhibitions annually in collaboration with Cromwell. Consequently, this exhibition forms part of Bavan Gallery's annual program in London. Although currently focused on London, Bavan Gallery might have plans to expand their exhibitions to cities like Seoul and others, which will be announced in due course. This exhibition was not tied to any specific art fair.

- It appears that there is a growing interest among Iranian galleries in holding exhibitions in London. Does Bavan Gallery plan to continue its exhibition activities there?

I believe so. The gallery has such plans in its mid-term or even long-term agenda. To answer the first question, London is one of the world's art capitals. Major auctions are held here, and there are numerous diverse museums operating in the city. Being present in London is always highly desirable, and all galleries aspire to have a presence in this city.

- In the major auctions held last month, works by Iranian artists were included. Was there a specific purpose for scheduling this exhibition to coincide with Christie's and Bonhams' Middle Eastern auctions? Generally, what impact does this timing have on the sale of exhibited works?

For us, this overlap was not predetermined, as the exhibition was planned in advance. However, I think the timing of both events does not have a negative effect. If there is another exhibition held alongside the auction that aligns with it, it helps buyers and collectors who follow the auctions. I find this overlap interesting and believe it can actually benefit both the buyers and the organizers.

- How long did it take to curate this exhibition?

I think we worked on the exhibition for almost two months. The idea for the exhibition had been proposed long before, and we had been working on it; however, once the exhibition date was finalized and we needed to start gathering the artworks, it took about two months of intensive effort. The theme of this exhibition covered a broad topic in Iranian visual arts. While we were familiar with it, it was important for us to showcase high-quality works. Thus, a significant part of our work was focused on achieving this goal.

- Who is the primary audience for this exhibition? Is it Iranians living in London or the artistic community and people of England in general?

I would say our primary audience consists mainly of Iranians; however, as I mentioned earlier, the Cromwell Collection itself accommodates several galleries. For example, there is currently an exhibition of modern and contemporary Moroccan art being held in the adjacent gallery. Our exhibition coincided with theirs on the opening night, which was noteworthy because visitors had the opportunity to experience both exhibitions. It presented art from two different countries and periods, enabling visitors to make comparisons and fostering dialogue. Many of the visitors to this collection may not be familiar with Iranian art initially, but upon visiting our exhibition, they become acquainted with it and find it quite intriguing. This discourse occurs not only among those already knowledgeable about Iranian art but also among individuals who visit the collection for various reasons.

- How would you assess the market for Iranian artists in London overall?

I believe the market is quite strong, not only for Iranian artists but also in the broader art market context, London has always been a unique hub. It has been particularly influential for Iranian art. As I mentioned earlier, with major auction houses like Sotheby's, Christie's, and Bonhams holding auctions dedicated to Iranian and Middle Eastern art throughout the year in this city, it's clear why London holds such prominence and why artists choose to exhibit here.

- Considering your experience in curating exhibitions both inside and outside of Iran, do you see any differences between curating for a domestic audience compared to an international one?

I don't see a significant difference. It depends on whether the curator prefers to work with local artists where they reside or prefers to introduce the art of one region to another geographical location. When working within Iran, factors like the Persian language and understanding of the local culture are important, whereas when taking an exhibition to another place, you need to be familiar with the language and cultural dynamics of that country. The challenge, in my opinion, is that you can't rely solely on the culture you come from. You need to build a cultural bridge, which requires a mutual understanding.

- Considering that you have translated the book "A Brief History on Curating" by Nazar Publications into Persian, how do you evaluate the overview of curating in Iran? What is your opinion on the status of curating in Iran in terms of its level or adherence to international standards?

I don't see myself in a position to give a specific opinion on this matter. Nonetheless, we have many top-notch Iranian curators who work both within Iran and abroad. There are numerous names, making it difficult to mention them all. Iranian curators are of a good standard; however, unfortunately, in recent years, due to travel restrictions, the pandemic, economic and political challenges, the art scene in Iran has been affected by these issues. Perhaps the vibrancy that existed before is not present in the Iranian art community right now, and political and social problems have had negative impacts on the arts. Despite all this, curators are still doing their work. I hope this trajectory won't be halted, and this dynamism continues to exist.

- In a conversation you had with Etemad newspaper last year, you mentioned that "the profession of curation, in its classic definition, is a theoretical and idea-centric pursuit, not an economic one." Apart from its classic definition, have other definitions emerged to address contemporary needs that present it as economy-centric?

Certainly, it has indeed emerged. Just like any other profession, even a university professor must earn a living, and economic considerations are inseparable from any profession. Therefore, in addition to engaging in cultural and theoretical activities, economics should also be considered for curators.

What we traditionally understand as the profession of curation is museum-based activity; it's what a curator does for an art institution, and then they may venture into commercial spaces where private galleries are involved. The definition I provided, which may have been further elaborated in recent books, centers around how curators engage in a form of deep cultural cultivation through their work in museums. One could say they play a role similar to archaeologists; it's a kind of artistic archaeology through which we can interact with contemporary and modern art while maintaining a historical perspective.

Therefore, undoubtedly, there is an economic aspect, and curators operate within the art market. However, it has unfortunately become common to primarily define curatorial activity in economic terms, whereas this perspective is inaccurate and cannot be applied to all curatorial activities. We must certainly consider its non-economic, theoretical, and art historical aspects as well.

- You have also mentioned in the same conversation that "the internet has democratized and made curation a universal profession. Nowadays, everyone has a page on social networks and, in a way, is curating by producing and selecting content for that page." Do you think this trend ultimately helps the field of curation, or will it eventually harm it?

I don't believe they necessarily conflict with each other; in other words, they don't harm each other. What we understand as the art of curation involves four main tasks. One aspect is selecting and acquiring artworks. Another involves writing about the artworks, including cataloging, providing information for museums, and writing articles. Then there's the conservation and protection of artworks, ensuring they remain undamaged and properly stored. The fourth aspect is displaying the artworks, which unfortunately seems to be where all our focus lies nowadays, and everyone thinks that curating is just about putting on an exhibition.

We shouldn't overlook the fact that curation is like an iceberg, with its tip being the display of works visible on the surface. However, the first three aspects are equally important because they lead to the selection and presentation of artworks.

In my opinion, the current understanding of curation revolves around organizing exhibitions curated by specific individuals. The same goes for the online space; individuals select some works and display them. If we deepen our understanding of curation and don't neglect the aspects I mentioned, it's not a problem if everyone becomes a curator. I don't think focusing more on this activity would weaken it, but we should understand its principles and foundations well.

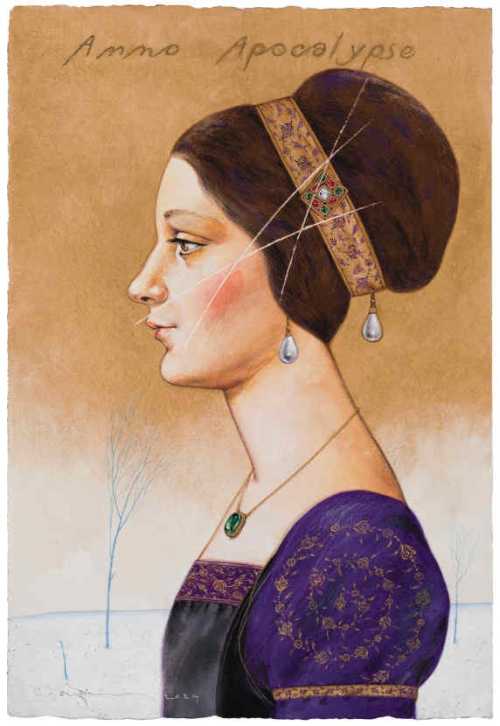

- Except for Aydin Aghdashloo's 2024 painting, the other artworks are closer in time to the modern era. Regarding Aghdashloo's piece from the "Memories of Destruction" series, its creation year creates ambiguity compared to the chosen theme of modern art for the exhibition. Is the selection based solely on the artist being considered modern, or do you classify this work as modern based on artistic criteria?

In this exhibition, there is another relatively recent piece, Mrs. Monir Farmanfarmaian's work from 2017. Unlike older pieces like Manoucher Yektai from 1952, our focus has mainly been on which period of Iranian art history the artist belongs to and how their position in Iranian art history is defined.

Aydin Aghdashloo is recognized as one of the artists of modern Iranian art. Born in 1940, most of his artistic activities started from the 1970s, which falls within the scope of modern art. Aghdashloo began the "Memories of Destruction" series around 1975, and the selected artwork for this exhibition is from that series. Although the artwork is from 2024, it still reflects the principles, statement, and interpretation of Aghdashloo's artistic thought from the 1970s. Therefore, we included this piece in the exhibition. If he had started a series that did not belong to that period, we couldn't have showcased it.