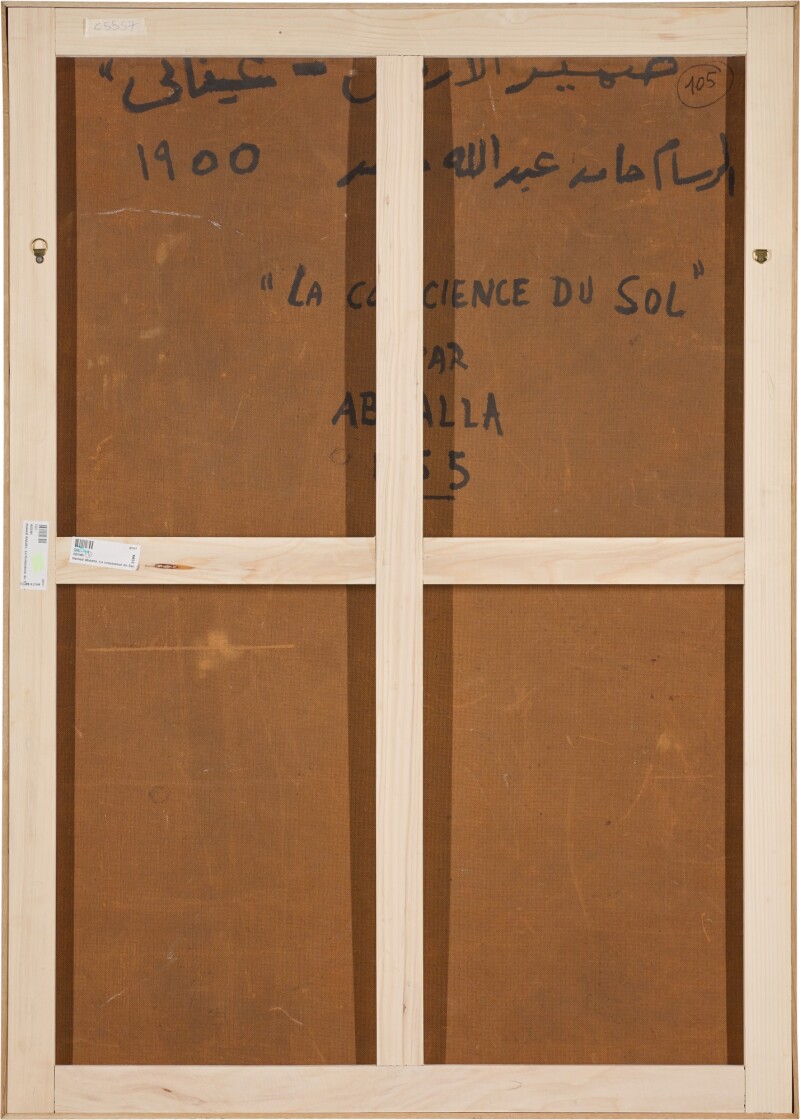

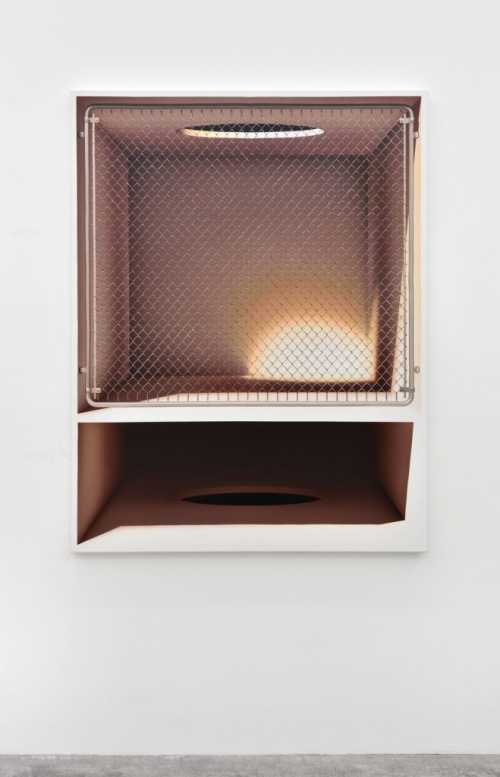

- La Conscience du Sol (The Consciousness of the Earth) 1955

- oil on board

- Painting

- 114.5 * 161.5 cm

- Signed, dated 1955 and titled on the reverseFramed: 163.5 by 116 cm. 64½ by 45¾ in.

23 March 2022

Estimation

£40,000

52,736 USD

-

£60,000

79,103 USD

Realized Price

£69,300

91,365 USD

38.6%

Artwork Description

“I aim at painting people for the people”. (Hamed Abdalla, quoted in Wall Street International 2018)

During the early phase of his artistic career, Hamed Abdalla strived to unveil the conditions of life in Egypt’s rural areas. In what he will later recall as “Signs of Egypt”, the young painter depicts his compatriots in a faithful yet simple style, already leaning towards expressionism rather than realism (Clare Davies 2018, p.286). Then in the 1950s, his designs undergo a stylistic shift, with colours laying flat over geometrical areas, delineating the drawing. In the present painting, Abdalla synthesises many of the artistic genres that influenced Egypt over time, mixing popular frescos, Islamic and Coptic arts or even Egyptian sculpture with tribal art. While claiming to paint with his spirit rather than his eyes, he gives to this fellah, an Egyptian farmer, the monumentality of a king (Wall Street International 2018).

This oil on cardboard was made in 1955 , at the same time as the establishment of Nasser’s government, where the fellahin’s condition was a major subject of concern in both cultural and political fields. Following revendications for a land reform, many farmers moved to the city to benefit from the economic boom. However, the development of urbanisation often obstructed agriculture, thus limiting their sources of income (El-Labban & Francis 2016, p.11). In Abdalla’s work, the fellah is represented as a peasant whose freedom depends on his land, yet constantly threatened to see his land expropriated. In his various paintings, such as Al-Amal (Hope) (1958), in the collection of Philippe and Olivia Maari, Cairo ; Lovers (1955), sold at Christie’s, London, 21 October 2014, lot 33; or Bahloul (1955), published in El-Labban & Francis 2016, p.11, the fellah stares back at the spectator both with an air of hope and rebellion.

“Abdalla’s fellah is a symbol of resistance, revolt, insurrection – he is like the closed fist of the prostrate body, which suddenly opens.” Morad Montazami in Arabecedaire, 2018, p.253

Abdalla’s artistic production, beyond its intellectual formalism, is bound to his unique perception of an often-overlooked world. His pieces demonstrate the artist’s acute understanding of these times and these lands, their people and their history (El-Labban & Francis 2016, p.22)

When interrogated on his affiliation to the Western modernist movement, and more specifically to Paul Klee, Abdalla always contested and even challenged what he called Western detours (Montazami 2000, p.1). Highlighting the Oriental and Egyptian elements that inspired, or were arguably appropriated, by artists such as Paul Klein, Henri Matisse or Henry Moore, Abdalla reclaimed their influences in his works, effectively turning them into trans-cultural images. For instance, Abdalla used Klee’s painting Drummer (1940) and subjected it to new indigenous American and African cultural influences (Montazami 2018, p.240). Among the works he thus created, our present lot, Soil Consciousness (1955), and the later eponymous larger painting from 1956 can be regarded as some of Abdalla’s masterpieces, for they generate a visual debate between Western modernism and contested folk aesthetics.

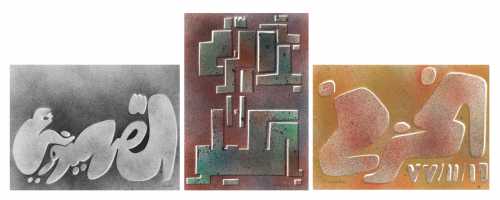

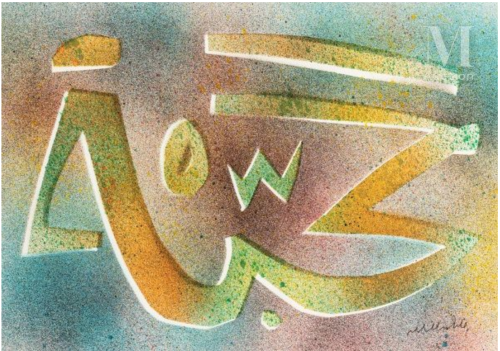

More lots by Hamed Abdalla

Al Mouhaba (love), from the Talismans series

Estimation

€5,000

6,094 USD

-

€8,000

9,750 USD

Realized Price

€11,700

14,260 USD

80%

Sale Date

Millon & Associés

-

16 June 2021

Realized Price

44,439 USD

Min Estimate

23,286 USD

Max Estimate

33,180 USD

Average Artwork Worth

+44.359%

Average Growth of Artwork Worth

Sales Performance Against Estimates

Average & Median Sold Lot Value

2021 - 2025

Performance vs. Estimate

2021 - 2025

Sell-through Rate

2021 - 2025

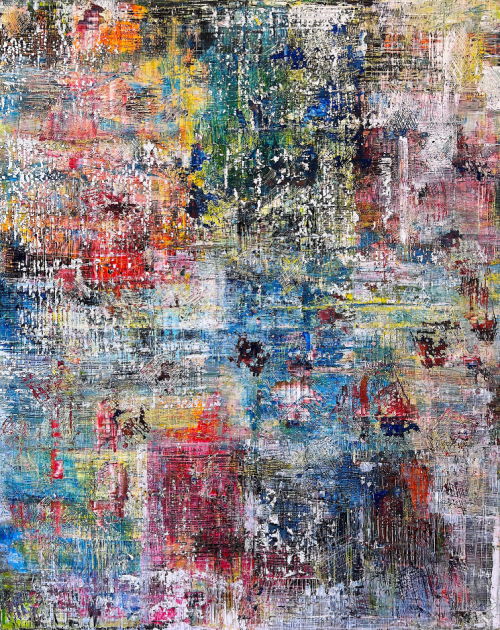

Similar Artworks

Sparks of Life

Estimation

£15,000

20,411 USD

-

£20,000

27,215 USD

Realized Price

£50,400

68,581 USD

188%

Sale Date

Phillips Auction

-

4 March 2022

Good Morning, Midnight

Estimation

$50,000

-

$70,000

Realized Price

$95,250

58.75%

Sell at

Sale Date

Sotheby's

-

14 May 2024