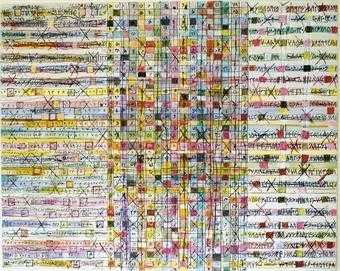

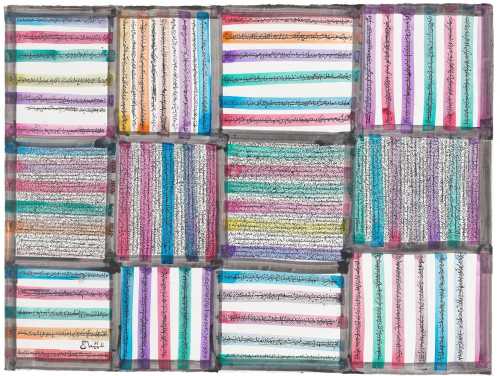

- Planets distances 1976

- acrylic and ink on canvas

- Painting, Calligraphy Painting

- 102 * 81 cm

- signed and dated 'Zenderoudi 76' and signed and dated in Farsi (lower right); signed, dated and titled 'Hossein Zenderoudi 1976 "Planets distances" ' (on the reverse)

Artwork Description

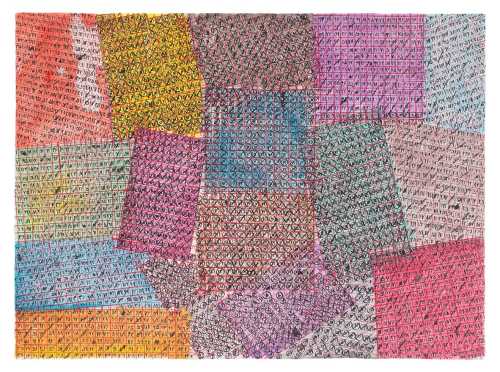

In the mid-1970s Zenderoudi produced a series of works based on Iranian talismanic charts of 19th century and earlier. These paintings are laid out in grid fashion with different coloured squares and numbers, letters and symbols which fill the squares recalling the prayers, codes and incantations on these charts. In so doing, Zenderoudi was revisiting one of his main sources of inspiration from the previous decade, which he recalls a major point of departure for the Saqqa-khaneh movement.

As he says

'As a teenager I often visited the Iran Bastan archaeological museum in Tehran. There were two display cases in the museum showing shirts which warriors wore underneath their armour. These white cotton tunics were completely covered with calligraphic texts and with tables of numerology. I was studying astronomy and that time, and also the various scientific instruments used to measure time and space, such as astrolabes. I was absolutely fascinated. The density of the black graphics on the taut screen of white cotton caused an intense feeling to well-up within me, and made me reflect beyond these visible objects and led me to question the condition of the mankind within the cosmos.' (Charles Hossein Zenderoudi).

Both in motif and spirit, this period of Zenderoudi's work shares much with his Saqqa-khaneh period of the early 1960s, which is sometimes described as a 'Spiritual Pop Art'. As explained in passage by Kamran Diba, the first director of the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art, 'there is a parallel between Saqqa-khaneh and Pop Art, if we simplify Pop Art as and art movement which looks at the symbols and tools of a mass consumer society as a relevant and influencing cultural force. Saqqa-khaneh artists looked at the inner belief sand popular symbols that were part of the religion and culture of Iran, and perhaps, consumed in the same ways as industrial products in the West" (Kamran Diba, "Iran" in Contemporary Art from the Islamic World, Widjan Ali (ed.), London, 1989).' 'The discovery of concepts and visual symbols of primitive religious rituals, in the form of prayers and spells devoid of traditional formalism excited the artist. The result was that he began to explore in his work a new vocabulary of beliefs' (Kamran Diba, preface in Saqqakhaneh , Tehran, 1977 cited in Shiva Balaghi, "Iranian Visual Arts in "The Century of Machinery, Speed and the Atom": Rethinking Modernity", in Shiva Balaghi and Lynn Gumpert (eds.), Picturing Iran: Art, Society and Revolution, New York , 2002, p. 25).

As he says

'As a teenager I often visited the Iran Bastan archaeological museum in Tehran. There were two display cases in the museum showing shirts which warriors wore underneath their armour. These white cotton tunics were completely covered with calligraphic texts and with tables of numerology. I was studying astronomy and that time, and also the various scientific instruments used to measure time and space, such as astrolabes. I was absolutely fascinated. The density of the black graphics on the taut screen of white cotton caused an intense feeling to well-up within me, and made me reflect beyond these visible objects and led me to question the condition of the mankind within the cosmos.' (Charles Hossein Zenderoudi).

Both in motif and spirit, this period of Zenderoudi's work shares much with his Saqqa-khaneh period of the early 1960s, which is sometimes described as a 'Spiritual Pop Art'. As explained in passage by Kamran Diba, the first director of the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art, 'there is a parallel between Saqqa-khaneh and Pop Art, if we simplify Pop Art as and art movement which looks at the symbols and tools of a mass consumer society as a relevant and influencing cultural force. Saqqa-khaneh artists looked at the inner belief sand popular symbols that were part of the religion and culture of Iran, and perhaps, consumed in the same ways as industrial products in the West" (Kamran Diba, "Iran" in Contemporary Art from the Islamic World, Widjan Ali (ed.), London, 1989).' 'The discovery of concepts and visual symbols of primitive religious rituals, in the form of prayers and spells devoid of traditional formalism excited the artist. The result was that he began to explore in his work a new vocabulary of beliefs' (Kamran Diba, preface in Saqqakhaneh , Tehran, 1977 cited in Shiva Balaghi, "Iranian Visual Arts in "The Century of Machinery, Speed and the Atom": Rethinking Modernity", in Shiva Balaghi and Lynn Gumpert (eds.), Picturing Iran: Art, Society and Revolution, New York , 2002, p. 25).

Realized Price

100,337 USD

Min Estimate

60,720 USD

Max Estimate

84,601 USD

Average Artwork Worth

+63.951%

Average Growth of Artwork Worth

Sales Performance Against Estimates

Average & Median Sold Lot Value

2021 - 2025

Performance vs. Estimate

2021 - 2025

Sell-through Rate

2021 - 2025

Similar Artworks

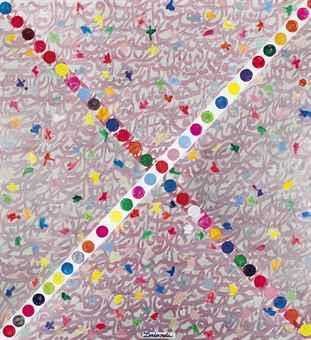

Untitled (Talismanic Charts)

Estimation

£15,000

18,654 USD

-

£25,000

31,091 USD

Realized Price

£35,840

44,572 USD

79.2%

Sale Date

Bonhams

-

24 May 2023

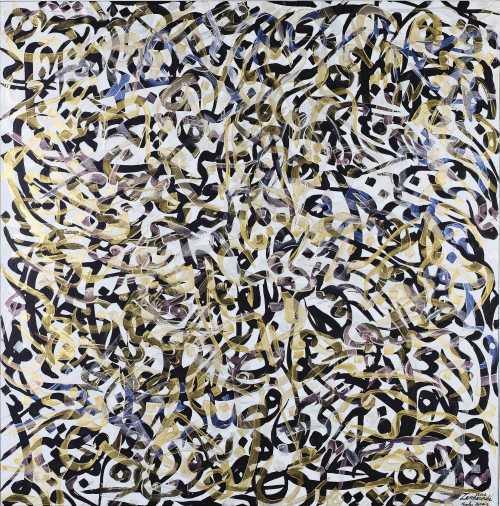

Untitled (Window)

Estimation

£15,000

18,654 USD

-

£25,000

31,091 USD

Realized Price

£40,960

50,939 USD

104.8%

Sale Date

Bonhams

-

24 May 2023